CURATOR’S STATEMENT

Zoë S.

Blackness and disability should be studied in tandem just as much as they are studied separately. The interconnectedness of racism and ableism — and the unique experiences of those who are both Black and disabled — offer a strong foundation for much needed societal commentary. This is especially true when observing these identities in police brutality discourse. Black autistic existence is complicated by the sheer fact that ableism and racism are even more potent when combined, and Black existence is complicated by the fact that an anti-Black police state creates disability in the Black community. It is in fact impossible to separate Black and disabled identities in America. This project sheds light on that inseparability through the lens of police brutality and the accompanying Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

I selected this topic because police brutality is at the forefront of many Americans’ minds right now, and I have seen countless hashtags attempting to stress the issue’s intersectionality. From the ever popular #BlackLivesMatter, I have seen #BlackTransLivesMatter and #BlackWomensLivesMatter, for instance. One hashtag which I had not seen until taking this class is #BlackAutisticLivesMatter. While the intersectional movement for Black rights and autistic rights exists, and the hashtag can be found on various social media platforms, it has not entered mainstream discourse in the same way that other variations have. At a time when more light is being shed on the unjust nature of police interactions with disabled people (think: Elijah McClain, Isaias Cervantes, and Linden Cameron), topics such as these are very pressing: intersections between Black and autistic identities, ways in which Black autists experience racism and ableism, and the unique nature of interactions with autistic individuals. Finally, I propose that police brutality is an especially promising jumping-off point because it creates a reality in which Blackness and disability may be synonyms.

I searched for media posts with the intent of choosing straightforward images that conveyed nuanced topics. These are most accessible in terms of length, language, etc. while also touching on complicated notions, leaving room to expand on the subtext and further implications of the seemingly simple image. Some posts are very brief and easy to comprehend, but in their simplicity they sacrifice necessary nuance. Others are detailed and thought-provoking, but their structure is such that anyone who is not in the mood to read an essay-like post will scroll past. My goal was to avoid both of those scenarios, which is why the posts are succinct yet compelling.

The written portions of this page consist solely of dark text against a light background; images with text are also followed by high-contrast black-and-white versions. All blocks of text/images follow one below the other; the page is organized entirely vertically. Each new section begins with the title (enlarged, bolded, and capitalized) and ends with a separator. I have also linked voice recordings for my media posts and writing. The sections all follow the same format, and I include both images and hyperlinks for each media post and article that I reference. This method serves three purposes: ensuring that viewers can refer to my chosen media even in the case that the link ceases to work in the future, attaching a visual to each discussion, and maintaining a consistent layout for my audience. It is my hope that my intentionality in putting together this page will make it more accessible.

BLACK AUTISTIC LIVES MATTER

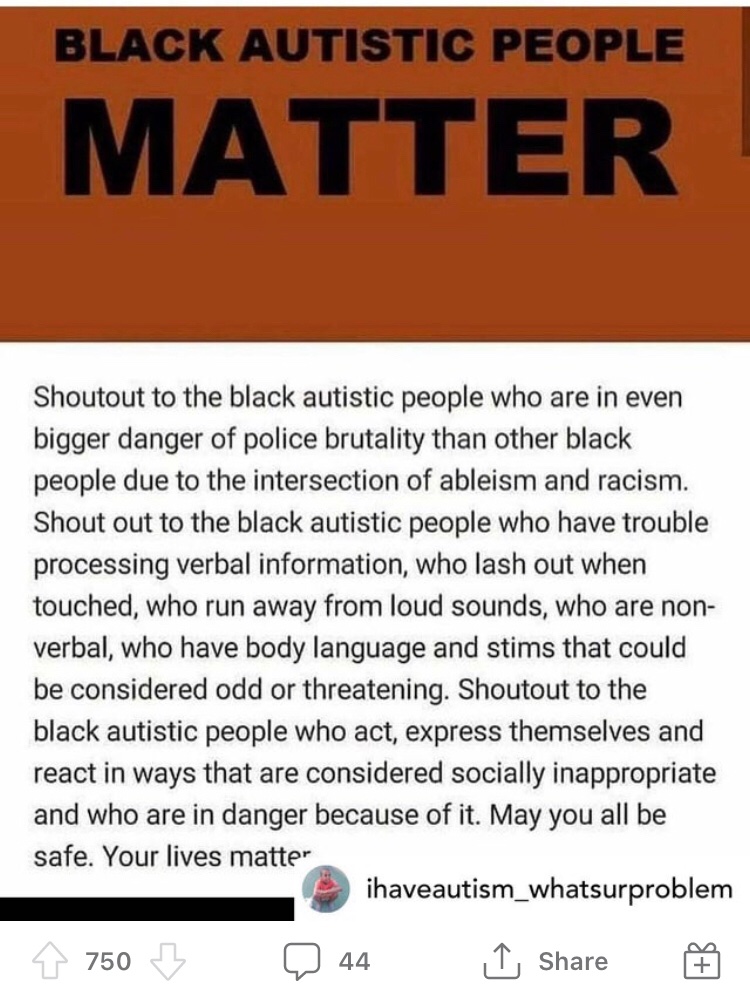

Source: Reddit post by u/AntiAbleism

This post is shared on Reddit by the user u/AntiAbleism, and it speaks to a broad internet audience. The account does not have a photo or bio section that provides further context regarding the identity of the post’s author. The image includes the word “Autistic” in the popular phrase “Black Lives Matter” which is a preview to the rich caption underneath. The first sentence touches on a topic we have studied that is especially relevant in our current society. Police brutality, like race relations and systemic racism in general, is a hot topic that often neglects intersections with disability studies. This caption points out the compounding layers of disadvantage that affect black Autistic people by using pointed language like “Black autistic people who are in even bigger danger.” The post also touches on characteristics of autism; it lists behaviors that are not specific to Black autistic people but prefaces with “shout out to the Black autistic people,” so as to remind the audience that these things apply to Black people too. In the same way that it addresses the fact that disability is a missing piece in race discussions, this post also subtly addresses the fact that race is a missing piece in disability discussions. At the same time, the author simply aims to clarify that the behaviors associated with autism are not threats but forms of self-soothing, self-protection, and self-expression: “that could be considered threatening.” The author points out that stigmatized behaviors which the neurotypical world will often associate with feelings of fear and danger are natural responses to a world that is not welcoming to neurodiversity. I also noted that this image was posted ten months ago, which was July 2020, during the heat of last year’s civil rights unrest. The historical context, combined with the astute but easy to understand language, make this post a great jumping off point for my discussion of intersectionality – especially between Blackness and autism.

KIND:PASSIVE AS ANTI:ACTIVE

Source: Instagram post by @ximemilagros

This graphic is posted by @ximemilagros on Instagram, an account belonging to Ximena Milagros Pérez Frankel. Her bio, made of short phrases and emojis, provides insight into her identity; she describes herself as a Peruvian mother living in New York City, a Master of Social Work student, an anti-racist, and a vegan, who cares about immigrant and domestic workers rights. Most of her posts consist of social justice information and statistics, with graphics and art being the popular methods of dissemination. This particular post, despite its simple and straightforward presentation, manages to tackle one of the most important pitfalls of our modern social justice movements. The original artist (@sylviaduckworth) combines a juvenile format (in terms of bubbly font, bright pastel colors, rudimentary drawings) with simple language to succinctly dissect a very nuanced topic: passive versus active stances. This nuance rose to the forefront in recent months as BLM popularized discussion of anti-racism — specifically, differentiating between being “not racist” and being “anti-racist”. Activists are pushing for intentional efforts to combat injustice, rather than settling for the complacency that has historically sufficed. As this post suggests, the importance of “anti” oppressive stances applies not only to race but to sexism, homophobia, transphobia, etc. In fact, the sentiment extends far beyond these few examples of oppression; the caption also includes: #antiracist, #antisexist, #antihomophobic, #antitransphobic, #antiableist, #antichildist, #antixenophobic, and #antihate. The image and hashtags are, in many ways, a call to action. They prompt the audience to reflect introspectively on their role (or lack thereof) in “anti” movements. Am I simply not a racist or am I actively anti-racist? Do I simply accept autistic people’s existence or am I actively anti-ableist? While many people might cite their avoidance of slurs or blatant hateful actions as signs of their acceptance, we cannot lose sight of the importance of real, tangible change. This is especially true now as social media makes it easy for people to simply like a post or share a statistic without truly practicing anti-racism and anti-ableism. Anti-ableist and anti-Black movements, at their core, must work to positively impact disabled and Black people’s material realities. To be “kind” is to refrain from making disadvantaged people’s lives harder; to be “anti” is to make their lives easier. The image’s creator pointedly writes at the bottom that “kindness without action is meaningless.” This sentence underlines the importance of actions that truly improve their lived experiences in concrete ways. Language is important, but our focus should still lie in real change. One way we may be actively anti ableist is through a commitment to fostering anti ableist spaces — the first step in transforming our entire society into an anti ableist space. Spaces like these are already being created — particularly in response to police brutality — and they work:

CRAFTING ANTI-ABLEIST SPACE WITH POLICE

Source: “For Parents Of Young Black Men With Autism, Extra Fear About Police”

This article focuses on policing, as it is written in response to the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson. It features a few women discussing their fears as mothers to Black autistic sons. They describe factors, such as inability to process verbal commands, that may put their sons in danger should they need to respond appropriately in a police encounter. The article touches on intersectionality in the BLM movement in a similar way to the first image I chose by displaying the various layers of disadvantage: first, the fear generated from the knowledge that one’s child may be in danger due to his Blackness, and second, the fear generated from the knowledge that his autism may make it even harder for him to understand the situation and remove himself from harm’s way. I find this source especially useful because it proposes a preventative framework that we have not discussed: creating intentional learning spaces for police and autistic individuals/families. One such program is being implemented by the LAPD, and it is aiding both police and autistic people in understanding encounters in which law enforcement demands/actions may be hard to understand, and Autistic behaviors like stimming and avoiding eye contact may be perceived as threatening. In all, the article I chose serves to both enrich my BLM-autism discussion as well as provide an outline for positive steps moving forward.

COMPOUNDING BURDENS

Source: TikTok post by @naiab1005

This video is posted by @naiab1005 on TikTok. Naia’s bio informs her audience that she uses she/her pronouns and that she is Black, autistic, and a member of the LGBTQ+ community. Unlike many of her other videos in which she speaks into the screen, this video includes text accompanied by an automated voiceover. This format may make it more accessible to some, although I am not sure that is her reason for refraining from her usual filming style. Because the topic being discussed is rooted in a feeling of fatigue, I suspect this style reflects her state — being so depleted that it is easier to write her thoughts and have the phone read them rather than explain them herself. This video enriches my discussion of intersections between anti-Black police violence and autism from a new angle. Sources I dissected prior to viewing this video focused on the added layer of danger in police interactions that arises when a person is autistic. Naia’s TikTok focuses instead on the general mental toll of being both autistic and a member of this race so often subjected to police brutality. The video was posted on 1 April 2021, and begins by highlighting the historical context: “Today we’re entering the fourth day of the Derek Chauvin trial. Today is also the first day of autism awareness month.” This not only situates the video in time, but draws viewers’ attention to an overlap which they may not have otherwise considered. The video then states, “I know what you’re thinking: what do these two events have to do with each other?” Here, she prompts her audience to begin considering the same types of questions I investigate in this project. The rest of the video explains why this time is especially hard for her. She describes her Black and autistic identities as clashing forces, making this particular period especially tiring because she must relive the collective trauma of police brutality as the trial is covered in the media while also facing microaggressions pertaining to her autism. This post sheds light on another way in which Black and autistic identities compound to make the reality of police violence even more harsh, burdensome, and exhausting.

ANTI-BLACKNESS AS A VEHICLE FOR DISABILITY

Source: “When black death goes viral, it can trigger PTSD-like trauma”

Naia’s discussion of trauma and mental toll also informs relevant discourse on the effects of police brutality on Black individuals’ health. Its effects are creating disability. This idea is expanded on in an article written by Kenya Downs, the digital reporter and producer for PBS News Hour’s Race Matters. Down speaks about the long-term health effects of the trauma that results from these constant police shootings. Specifically the imagery — which is circulated easily, widely, and repetitively, thanks to modern technology — has PTSD-like effects: “Graphic videos (which she calls vicarious trauma) combined with lived experiences of racism, can create severe psychological problems reminiscent of post-traumatic stress syndrome.” The article explains that this vicarious trauma, when combined with everyday racism, fosters fear, anxiety, alienation, isolation, and general race-based trauma. It goes on to discuss a 2012 study which found that Black Americans reported experiencing discrimination at higher rates than any other ethnic minority and also had the highest PTSD prevalence rate. Mental illnesses like PTSD and symptoms that result from trauma can be disabling and debilitating. And the health effects are not limited to PTSD: “It can lead to depression, substance abuse and, in some cases, psychosis. Very often, it can contribute to health problems that are already common among African-Americans such as high blood pressure.” Many Black people are being disabled through declining physical and mental health due to their exposure to instances of police brutality — lynching by gunshot. If this is true now, then the same must apply to the centuries of lynching by hanging which are so characteristic to United States history. If watching a video of a Black person being shot can produce such negative health repercussions, then one can only guess the effects of a Black person being made to witness their kin be hanged before an audience. As the article states, America’s racist history becomes crippling as it is passed down generationally. In this way, Blackness is not only harder to navigate when it includes disability, but Blackness (because it exists in an anti-Black society) becomes disability. Police brutality’s effects on Black health are proof enough. While it may not specifically cause autism, generational trauma is still relevant to the Black autistic community because it may mean that they live with more disabilities than they are aware of: autism and the unnamed disability(ies) that results from having exposure to these lynchings.

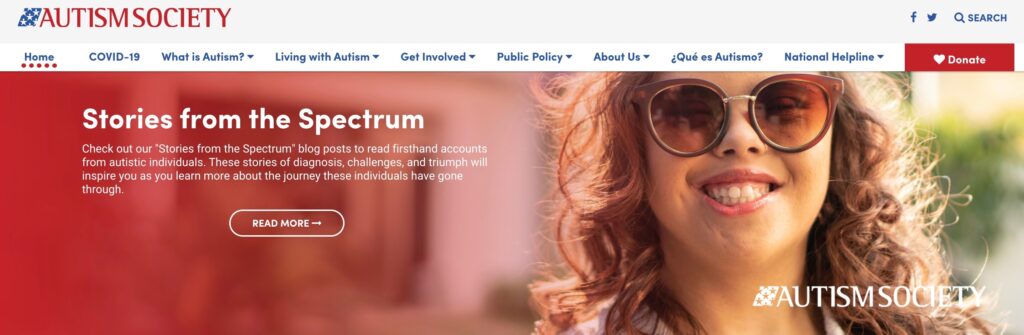

THE AUTISM SOCIETY: CONNECTIONS AND STATISTICS

Source: The Autism Society

The Autism Society, founded in 1965 by Dr. Bernard Rimland and Dr. Ruth Sullivan in collaboration with other parents of autistic children, describes itself as “the leading source of trusted and reliable information about autism.” It hosts a national autism conference and spearheads many initiatives to improve the lives of autistic individuals. They have pushed for inclusive legislation, created a database for resources, and established a National Contact Center to provide guidance.

It is difficult to find statistics for this project, as this particular intersection has not been a part of mainstream discourse/observation for very long. But The Autism Society’s website was helpful. While they did not make a statement on the intersections between (anti-Black) police brutality and autism, the Society did publish a piece on its website following the murder of Linden Cameron. Cameron, a white thirteen-year-old with autism, was shot by Salt Lake City police in 2020 after his mother called for crisis assistance. In their response to the occurrence, the Society noted the following statistics: one in five young adults on the spectrum will come into contact with the police before age twenty-one, disabled people are five times more likely to be incarcerated than those without disabilities, and lack of police training causes more injuries/fatalities in these vulnerable populations. These are all overlaps that cannot ignore the factor of race.

The final paragraph reads: “The Autism Society of America is prepared to help law-enforcement departments to learn how to promote and expand best practices for successful law enforcement interaction with people with disabilities, including training on behaviors such as wandering, different communication styles, and stressful reactions to physical prompts and restraints or environmental stimulation. The Autism Society calls for immediate transparency and accountability from the Salt Lake Police Department, and city officials, and stands by ready to assist with proper training and de-escalation techniques.” It seems that they are ready to bridge the gap between the ideas I dissect in this project and autistic people’s lived experiences!